I Was (Kind Of) Wrong About The Tortured Poets Department

Over a year after its release, and on the cusp of her upcoming 12th studio album, I decided to reevaluate Swift's divisive heartbreak opus. My feelings, much like the album, are complex.

“Time, doesn’t it give some perspective?” - Taylor Swift

Taylor Swift is an artist whose musical career was actively developing alongside my own burgeoning relationship with music. The presence of her music in my life as a child and young adult was undeniable- she has a catalog of hits spanning as early as her debut era, which began in 2006, when I was only seven years old. Without ever truly choosing to listen to her music of my own accord, she had unwittingly become the soundtrack to many of my childhood memories. Her earlier tunes echoed out of the speakers of my mom’s mini-van, and her mid-career albums, namely Red and 1989, spawned hit singles that filled the dancefloor at many a middle school dance. Aside from the indomitable presence of her music, she had also grown to become an omnipotent figure in the fledging tabloid industry and developing social media news cycle. Her notable feuds (as they were then presented) with Kanye West, Kim Kardashian, and several ex-boyfriends often overshadowed the role her music played in mine, and many other passive listeners’, lives. As someone who wasn’t particularly interested in either her personal life or musical output, my general attitude towards Swift was one of apathy. When I was 15 (pun not intended, but I’ll take it) and met the people who would go on to become my lifelong best friends, that all changed.

Two of my best friends are as much of an OG Swiftie as a person can be. Growing up, their relationship to her and her music was very different from mine- they owned all of her albums, went to see her on tour, and studied up on the endless lore that still surrounds her and defines the bulk of her output. They could not fathom that I felt so indifferently towards who they still consider to be the artist of their lives, and did everything they could to open my eyes to Taylor Swift, musical genius extraordinaire. My initial resistance eventually gave way to curiosity, which then led to a genuine appreciation for Swift and her artistry. This epiphany aligned with the release of reputation in 2017, and I’ve been tuned in ever since.

The shift in mine and Swift’s relationship also aligned with what would become a significant increase in her musical output, starting with 2019’s Lover, and never really stopping until the release of The Tortured Poets Department in 2024. In this span of time, Swift released five albums of original music, a live album and Disney+ behind-the-scenes special, and four rerecorded versions of several of her first six albums. She would also embark upon the years-spanning Eras Tour and release its accompanying concert film amidst the release of all of this music. For a converted Swiftie like myself, this was all a bit much to digest. And for the general public, this reached a point of excess that contributed to a shift in media coverage of Swift that echoed the ire directed at her in her early years. I found myself starting to experience some Taylor Swift fatigue due to the influx of new music, endless stream of Eras Tour content, and round-the-clock media coverage of Swift’s personal relationships. This fatigue soon circled back to the indifference I initially felt towards Swift. All this to say that at the time of The Tortured Poets Department’s initial release, on April 19th, 2024, I wanted no part of it.

I listened to the standard edition of The Tortured Poets Department a few times before casting my initial judgements, but I can’t say that I ever truly gave it a fair chance. I gave The Anthology tracks even less attention; I think I might have listened to them twice before shelving the record for over a year. From what I heard, although briefly, I wasn’t a fan. The material sounded like more of the cut-and-paste synth-pop that Swift and Antonoff had polished to an unfathomably smooth sheen on Swift’s previous album, Midnights. Critics were divided about the album as well, with many sharing my initial assessment, while others felt that the record was full of hidden gems that required a little extra care and attention on the listener’s part in order to recognize their true potential. At the time, due to a litany of reasons both understandable and unfair, I had no interest in putting in that effort.

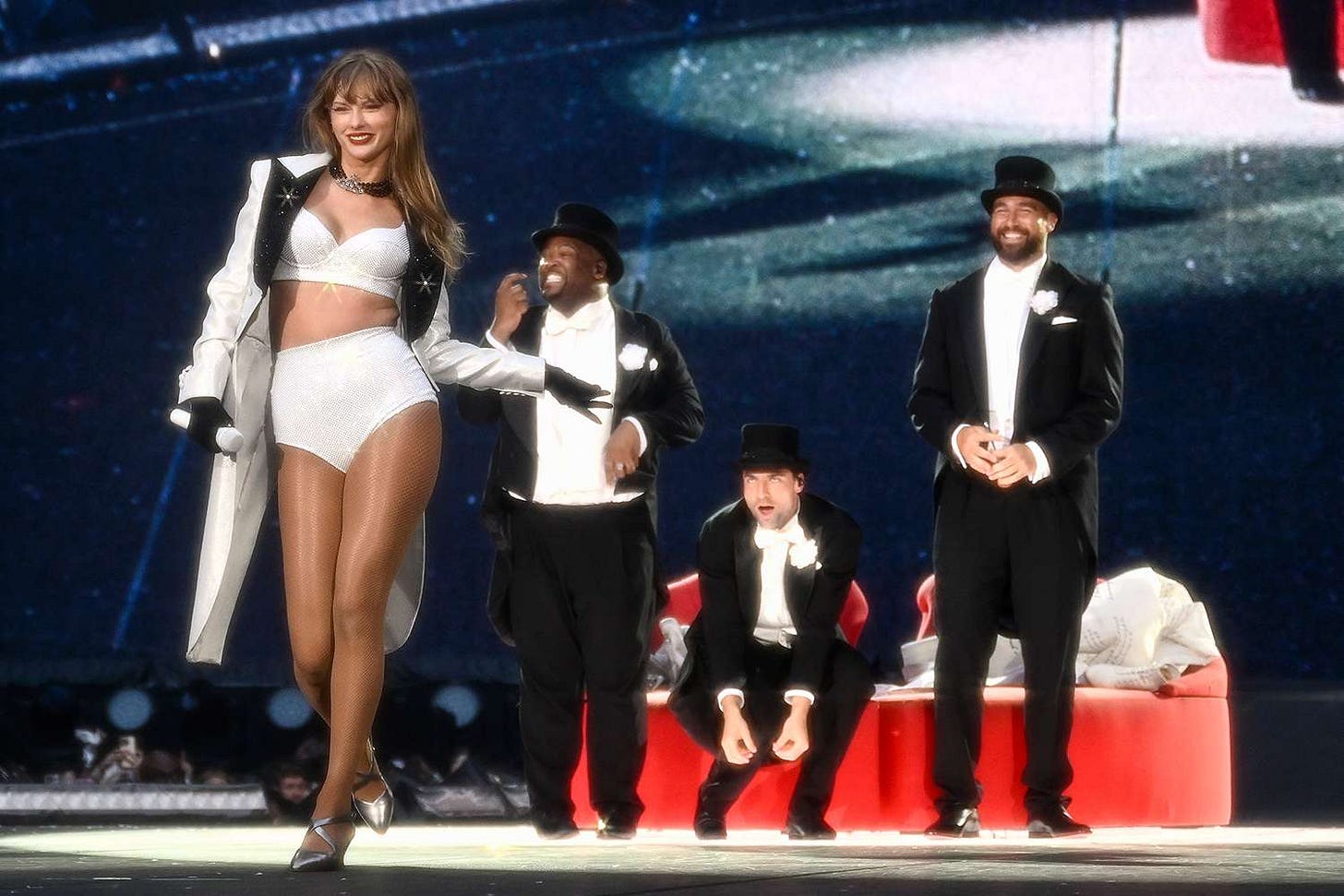

The first of two major reasons that I now recognize as the motivation behind my complete dismissal of TTPD is one that I know I was not alone in feeling at the time- I was tired of Taylor Swift. I recognize that the oversaturation of Swift in the media and online was not all her fault, but her creative decisions were definitely contributing to my lassitude. At the time of TTPD’s release, Swift was at the absolute apex of superstardom, with a ubiquity rivaling that of Michael Jackson at the peak of his fame. The Eras Tour was taking over social media, especially due to Swift’s “surprise song” segment where she performed a different deep cut at each show, whipping fans into a frenzy and giving them a reason to tune in night after night. She was also pumping out music at the speed of light, announcing an original or rerecorded album several times a year from 2019 onward, all of which would subsequently dominate the Billboard Hot 100 charts, and virtually any other music space that exists. As if this wasn’t enough fodder for the media machine, Swift was also going through a period of personal turmoil that coincided with this uptick in public consciousness. Her relationship with longtime partner Joe Alwyn came to an end, and she began a short-lived fling with The 1975’s controversial front man, Matty Healy. The dissolution of these relationships inspired much of the lyrical content across TTPD, as did the onset of her current relationship with NFL superstar Travis Kelce.

Swift has never been one to shy away from the spotlight, but this was a new level of attention, even for the most famous musician in the world. The quick turnover of these three relationships garnered a fair amount of misogynistic scrutiny about Swift’s dating history, a topic that has followed her since her teen years. It didn’t help that Matty Healy was in the midst of his own series of controversies due to racist remarks made about rapper Ice Spice, or that he has a laundry list of other controversies that were inevitably brought to light by his attachment to Swift. While this would eventually make for excellent lyrical content, it was a period of intense scrutiny for Swift that only heightened her exposure. If you weren’t already seeing her splashed across social media, you were now also encountering articles about her new contentious relationship from legitimate news sources. For someone like myself, who was only ever loosely interested in the interpersonal relationships that acted as the inspiration behind Swift’s music, this was just fanning the flame of a growing sense of Swiftie detachment.

In hindsight, I recognize that many of valid criticisms lodged at Swift for her decision to date someone who seemingly represented the antithesis of her moral leanings was drowned out by people’s desire to take down a woman that they deemed “too famous.” This negative coverage only increased when her relationship with Kelce began and made her a fixture of the NFL’s promotional strategy. Swift’s face was splashed across jumbotrons at all of Kelce’s games, presenting her to a new audience of sports fans who were less than welcoming. What was always a harmless attempt at supporting her partner was spun into a ploy for attention on Swift’s part, with many reveling in yet another opportunity to criticize a female musician at the height of her success. Again, this is not to say that Swift wasn’t also facing some valid criticism at the time- much of it surrounding the environmental impact of her frequent private jet usage- but it would be unfair to say that this coverage was honest and balanced. Swift’s newfound connection with the NFL created yet another avenue of exposure for the star, making it so that football fans across the country were discussing her for reasons totally unrelated to her artistic output.

The release of The Tortured Poets Department fell smack in the middle of this era of intense public scrutiny and, as she is wont to do, Swift took full advantage of her role as the world’s most famous martyr. Any of the reasonable criticism that existed among the sludge of misogynistic ire was reinterpreted through her artistic lens as evidence of her position as a woman scorned. I was already finding it hard to digest the public obsession with Swift, and her attitude towards the condemnation made it even harder to feel sympathy for her. Of course, this assessment is unfair on my part and relies on the predication that the most successful among us don’t experience the same human emotions that the rest of us feel. However, I do think acknowledging the role Swift plays in shaping her public perception, and her willingness to use it as a promotional tactic, is vital to understanding why I was less than thrilled with what I assumed would be an album full of material that reflected her self-appointed martyrdom.

This brings me nicely to the second major reason why I held such a negative opinion of The Tortured Poets Department for so long- I had been growing increasingly frustrated with the quality of Swift’s music leading up to its release. I know I am not the first person to share this opinion, especially considering the fact that even some of her biggest fans have expressed their discontent with the quality of her recent releases. My disappointment largely stems from the rerecording project that Swift decided to take on as a result of her catalog being purchased out from under her by Scooter Braun in 2019. I take no issue with Swift wanting to own her masters, in theory- I recognize that many musicians feel that owning their masters is essential to making them feel as if their work is truly their own. What I do take issue with is the way Swift went about the project, and the overall quality of the music it produced. The first two rerecorded albums that were released, Fearless (Taylor’s Version) and Red (Taylor’s Version), do an excellent job capturing the essence of the original compositions while polishing up some of the rougher edges of the decades-old material. My issue with the rerecordings originated with Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), and reached a fever pitch with 1989 (Taylor’s Version). Both of these albums are poorly produced, lazily recorded, and taint the legacy of what are two of Swift’s most classic records. Swift and Antonoff dulled down the intensity of many of the albums’ most fiery moments with their propensity for inoffensive synth-pop. The original version of Speak Now is defined by its youthful vigor and teenage angst; the rerecording smooths out the jagged edges that made the original so special.

And then we have Midnights, Swift’s tenth album of original material following the magnificent one-two-punch of sister albums folklore and evermore. Where folklore and evermore saw Swift diving headfirst into uncharted sonic territory, pairing her prolific lyricism with wistful, textured alternative production, Midnights is a retread of familiar, and far less impressive, territory. There is a lot to love about Midnights, primarily its balance of self-deprecating honesty and unrestrained fun. It is both introspective and euphoric, managing to never be too self-serious or not self-serious enough. Where the album loses me is in its production choices. Antonoff and Swift have developed their own sonic template made up of mid-tempo rhythms, heavy synthesizer use, and electronic drum patterns. At times, they employ the elements of this template to develop a cohesive soundscape. More often than not, the results sound sparse, tedious, and unfinished. Evaluating Midnights in retrospect does provide some clarity as to the direction Swift was attempting to go with the album, but doesn’t necessarily make me enjoy it any more.

Among my most unjustifiable reasons for being frustrated with Swift at the time is the fact that I was annoyed with Midnights’ triumph over SZA’s SOS for Album of the Year at the Grammys. I recognize that this is no direct fault of Swift’s, but she unfortunately suffered as a result of this win in my eyes. I did say that some of my reasoning was unfair, didn’t I?

For over a year, I dismissed The Tortured Poets Department altogether. I held no contempt towards the music itself, I just wrote it off as something that I had no desire to revisit. I was convinced of its position as a filler album in Swift’s discography- further evidence of her decision to prioritize quantity over quality. It didn’t help that the album fared poorly at the most recent Grammys and had seemingly fallen out of public favor quicker than any of Swift’s prior releases, even though it spent a record-setting 17 weeks atop the Billboard 200 albums chart. All of this led me to feel vindicated in my initial assessment of TTPD. So… what changed?

The short answer is also the least satisfying one- nothing, really. I can’t pinpoint what exactly made me lift my personal embargo and finally decide to give TTPD another chance. Maybe my Swiftie senses were subconsciously tingling (Swift announced her upcoming 12th studio album on the day that I began writing this piece). More than likely, I was just bored. I had always planned to return to TTPD when I felt like the time was right. I think, on some level, I harbored guilt for never giving it a fair chance- as someone who reviews music as a primary hobby, this was very out of character for me. And so began my official reassessment of The Tortured Poets Department. Here are my findings.

Much of what I originally felt about the album remains true to this day- it is overlong, indulgent, and one-note. Swift is known to forego editing down her projects; of her eleven studio albums, the standard editions of six of them run over an hour (if you factor in the deluxe editions, reputation is her only album shorter than 60 minutes). The rerecorded albums are another story, considering they contain all of the albums’ original and bonus tracks, plus the additional “vault” tracks that were written alongside the original albums, but never received an official release. The standard edition of TTPD follows suit, boasting a 65-minute run time. Though longer than most albums released in the current era, this is a perfectly acceptable length. What makes the album stand out as an exceptional exercise in indulgence is the album’s B-side of 15 (!!!) surprise-released tracks that arrived at 2am on the night of the album’s release. Swift employed a similar tactic with the Midnights (3am Edition), but that only added seven tracks to the album’s trimmer standard edition. The Anthology tracks brought TTPD to a whopping 31 tracks, making it Swift’s longest album to date. It was as if she couldn’t help but share every piece of music she created during the development of the album, rather than editing the project down to reflect the best of the bunch.

Because of the sheer volume of tracks on The Tortured Poets Department, it was inevitable that not all of them would be winners. This gripe was one that originally encouraged me to steer clear of the album- I just couldn’t fathom that a 31-track album could contain enough viable material to make sifting through the muck worthwhile. This reality came as a bit of a shock, but there is actually quite a bit of solid material spread across the album. Most of it lies within the original 16 tracks; I find the folksier Anthology tracks to be less interesting by comparison, highlighting Swift’s storytelling ability but sacrificing much of the sonic depth of the album’s first half in favor of lyrical density. The atmospheric synth-pop that dominates the first half of the record didn’t impress me at first, mainly because I viewed it as a retread of the same territory that I previously didn’t enjoy from Midnights. This is where I went wrong.

The way the synths are employed across TTPD is cinematic, deftly reflecting Swift’s emotional state at the time of the record’s inception. The sparseness of tracks like “So Long, London” allow Swift to play with her cadence and delivery in a way that emphasizes the lyrical intensity of the track while still creating intrigue for the listener. Her voice remains slightly behind the beat, out of breath and exhausted, falling behind much like a lover at the end of their rope in a flailing relationship. The eerie Western influences that permeate “Fresh Out The Slammer” and “I Can Fix Him (No Really I Can)” bring to mind the isolation and loneliness depicted by the songs’ evocative storytelling. There’s an unsettling feeling that runs through much of the album’s material that brings to mind the album’s visual imagery- the sole music video Swift released, for lead single, “Fortnight,” was rife with gothic, dark academic visuals- and places the listener squarely in the mindset of someone on the brink of collapse following the disillusion of a tumultuous relationship.

This is not to say that the album’s production is always effective. There are moments towards the back half of the first disc that take the slow, brooding angle too far- namely “loml,” which drones on without saying anything we haven’t already heard. Swift hits other lyrical snags as the album progresses. With 31 tracks, almost all of which detail the same relationship, you’re bound to reach a point where everything that could possibly be said has already been said. Much of The Anthology’s lyrical content feels repetitive, even when Swift attempts to convey her message through metaphors and other framing devices. This isn’t as much a criticism of Swift’s songwriting as it is of her inability to edit down her work. She would not be running into this problem if she had chosen the best 15 or so tracks and released one very solid, albeit shorter, album.

While we’re discussing lyrics, we might as well address the Charlie Puth-shaped elephant in the room. Upon release, TTPD was instantly ripped apart for its “cringe” lyrical moments, including the aforementioned Charlie Puth reference from the title track, along with other cherry-picked lyrics from “I Hate It Here” and “So High School.” I’ll admit that I was also swayed by the social media buzz surrounding some of these more questionable lines, especially because I was unfamiliar with the content from most of the second disc. Some of the lyrics that received criticism are actually pretty cringe- I can’t find it within myself to justify the inclusion of that Charlie Puth lyric, and I struggle to get through the chorus of “Down Bad” without uttering at least a slight groan. However, most of the other lyrics that received criticism were simply lacking context. The Grand Theft Auto reference in “So High School” sounds strange in isolation, but makes perfect sense within the context of the track. Even the reference to, “the 1830s but without all the racists,” in “I Hate It Here” sort of makes sense in context.

I think a lot of this criticism, and that which surrounded the album as a whole, is an issue of perspective. Swift is one of the most earnest songwriters we’ve ever seen. Her music cannot be viewed through the lens of a cynic- that just isn’t how she operates. She takes herself, and her music, very seriously, evidenced by her songwriting. Tracks that I originally interpreted as obnoxious, like “I Can Do It With a Broken Heart,” carry a whole new meaning when I shifted my perspective. Yes, there are aspects of the song that are cliche, but that’s the whole point. Swift’s work across TTPD is so self-aware and insular that it is best viewed as a pastiche of Taylor Swift, the person and musician. Like much of the album’s tactics, this is also not always effective. “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” leans too far into Swift’s self-appointed martyrdom that it becomes silly, and “The Alchemy” and “thanK you aIMee” bypass winking irony and circle back to being insufferable.

Like much of my reasoning for initially dismissing The Tortured Poets Department, quite a bit of my initial assessment was unfair. I am not alone in this experience, as many professional critics have recently reevaluated the album and shed some new light on the very many needles hidden in plain sight within this haystack. I wouldn’t fault anyone for having a negative reaction to TTPD at face value- the combined effect of its 31 tracks and occasionally exhausting sonic cohesion was enough to put me off for over a year. There are flashes of brilliance throughout TTPD, some of which don’t reveal themselves to you immediately. If you’re someone who genuinely enjoys music, and is accepting of the fact that not all music is meant to “click” during your very first listen, I would advise you to give TTPD another chance. You might be surprised by what you find. I definitely was.

I didn’t like TTPD much that first weekend of release. It felt very long and self indulgent and I liked a few songs. By 6 months later, I could listen to 30 songs (I can’t stand thank you Aimee and will never get over that one). I Look in People’s Windows is my favorite anthology track.

Folklore and evermore finally grew on me literally in the last 2 months. I got really into exile because it was on The Summer I Turned Pretty and finally watched The Long Pond sessions.

this was such a well-written, detailed review that i couldn't stop reading till the end. i only became a more earnest listener of taylor swift when ttpd released after becoming friends with a someone who was a huge fan of hers, and i also wrote a review about it on my substack when it came out.

i have to agree with a lot of your thoughts - i definitely feel like all the songs in ttpd weren't a hit, but i was pleasantly surprised by the level of self-awareness she posed in each song, no matter how ostentatious it seemed to be. i like your analysis on how she takes herself seriously as an artist and therefore requires a listener who would also take her songs seriously, if even for a moment. overall, i really like your critical writing style and will definitely check out more of your reviews!